'Another sheep, mangled and bled out, her innards not yet crusting and the vapours rising from her like steamed pudding'.

The protagonist, Jake Whyte, is a hard woman to match the hard life of farming and shearing. She has a man's name, lives in a man's world, and descriptions of her strong arms and strong countenance make her an intriguing character: 'It's too hot, but I like the way the heat makes my arms feel like they're full of warm oil, and sweat runs down them in sheets soaking the sides of my singlet'. The unusual portrayal of a female shearer is attractive, and the references to Jake by other characters as a 'bloke' is nicely ambiguous.

The first third of the novel is full of pauses and threads hanging without elaboration, but as the rest of the novel unfolds we are given the full story of Jake's life and it isn't pretty. Wyld's descriptions of sex aren't gratuituous but are confronting, and if we are led to believe that the shearing shed can be a woman's world, we are under no illusion that for desperate young women trying to eke out a living, it is still a man's world: 'And as it goes, the sex is just the same for bored men as it is for over-excited men. I guess they've had the chance to really think about the things they'd like to do to a person'.

Jake dominates the novel, but secondary characters are given brief but engaging cameos: her teenaged friend Karen is a wonderfully eccentric buddy in Port Hedland, Don is a kindly farming neighbour, and Lloyd is a peculiar visitor to the farm, bringing with him kindness and a wry sense of humour. I wish there had been more of Lloyd in the book: he was the only lack of elaboration that disappointed me.

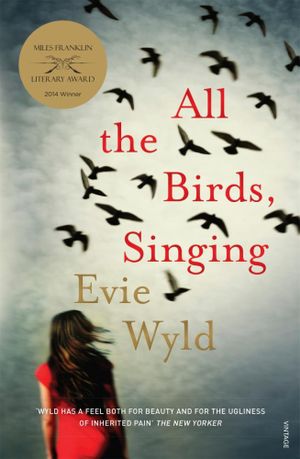

Evie Wyld was on the 2013 Granta list of Best Young British Novelists and this is no surprise given the sophistication of the ideas and imagery in this novel. Her residency in England may be assured now from her overseas success but I hope she travels back home to Australia more to write: she has a clever insight into the ugly beauty of our outback and the people who survive within it.

*This review is part of the Australian Womens Writers Challenge 2014